This is part two of the New Global Citizen’s coverage of the 2014 Net Impact Conference, “Breaking Boundaries,” held in Minneapolis, Minnesota in November 2014. The conference convened impact leaders from across sectors to forge unexpected alliances and explore creative solutions to some of the world’s toughest social and environmental problems. Read part one here: Can Global Business Feed the Word?

Humans are the world’s biggest social challenge. By 2050, 9 billion people will inhabit the earth. This was one most frequently cited statistics over the course of the three-day Net Impact Conference. The conversation focused broadly on the power of business to tackle the world’s toughest social and environmental problems, but in discussing the specifics, two facts featured prominently. First, the planet’s rising population is the biggest limiting factor on the world’s water, energy, and food supply. Second, each of these challenges, though individually complex, is inherently intertwined. As water crises around the world threaten this critical relationship, companies at the intersection of food, energy, and water must proactively collaborate to manage risk and ensure the stable supply of these resources.

The Expanding and Complex Water-Energy Nexus

Water is a precious commodity in its own right, but it also plays a critical enabling role in energy production. It is used in power plant cooling and in providing the hydropower necessary for fossil fuel production processes, just two examples of how water is used in nearly every phase of energy production. Likewise, energy is necessary to extract and distribute water from aquifers for agriculture, for desalination, and of course in the distribution and heating of the water people drink, cook, and wash with every day. The strain of the earth’s rapidly growing population, water-intensive industries, and climate change on the world’s fresh water supply is creating immediate pressure on this water-energy nexus.

During Every Drop Counts: The Business Case for Water Stewardship, a panel at the Net Impact Conference, business leaders discussed new partnerships, practices, and tools that are changing the future of water stewardship. Douglas Baker, who spoke on the panel, is the Chairman and CEO of Ecolab, a global provider of water, hygiene, and energy technologies that serves the food, energy, healthcare, manufacturing, and hospitality markets. He identified six key water statistics that are guiding industries’ search for innovation and efficiency. According to global averages, 70 percent of fresh water is used in agriculture production, 20 percent by industry, and 10 percent for domestic use. By 2030, the world will need 30 percent more water, 40 percent more energy, and 50 percent more food.

Fortunately, water is a stable substance not easily transformed by the process of its use, differentiating it from resources like oil or liquid natural gas. The earth’s water supply is a captive system, so the current water endowment of the planet is finite yet vast. In fact, the greatest water challenge facing society is actually that the percent of freshwater available for use is less than one percent of the water on earth.

“By 2030, the world will need 30 percent more water, 40 percent more energy, and 50 percent more food.”

The World Bank predicts that, by 2025, water demand will exceed supply by 50 percent. That number is global, but in reality, it’s a very site specific challenge. In water stressed regions that number could be a 200 percent mismatch of supply and demand. “In other regions there will be plenty of water to meet all demand for the foreseeable future,” said Baker.

This challenge is not a new revelation, particularly for the private sector. According to a 2014 survey, 60 percent of U.S. companies indicated that water will affect business growth and profitability within five years. “By and large, almost every customer we work with wants to reduce their carbon footprint… But some act on it aggressively and some don’t. What we want to do is have the solutions to make it economical for companies to make water reduction a priority,” said Baker. Doing so can reduce and even eliminate the barriers companies face to taking action.

Ecolab’s solutions helped Hyatt Hotels save 73 million gallons of water in one year by making laundry operations more energy efficient. “You have to change the way work gets done,” said Baker. “Otherwise, you have theory and good intentions, but you have no actual impact.” Additionally, Ecolab’s work with the Dow Chemical Company saved 1 billion gallons of water and $4 million a year in just one Dow chemical processing plant in Freeport, Texas, enough to sustain the population of the town for three years, the equivalent of providing daily water use for more than 14.4 million people, based on the average daily water use estimated by the American Water Work Association.

In addition to Hyatt and Dow, companies like Coca Cola, Cargill, General Mills, Nestle, and Ford are among those with ambitious water reduction goals. The impact such companies have achieved is already significant, but progress extends beyond the four walls of a company’s manufacturing plant. “There is more work to be done,” said Baker. “While that progress is fantastic, it isn’t enough and it isn’t fast enough.”

The question remains, what incentives can encourage companies to more highly value water efficiencies in their business decisions, and pursue them more aggressively?

Pricing Water’s Business Value Incentivizes Better Water Management

According to Richard Mattison, Chief Executive Officer at Trucost, achieving greater gains in water resource management requires a clearer valuation of water’s worth. “There is a business mantra that goes: what is measured is managed. But I slightly disagree with that mantra because I think that a lot of things are measured in this world of big data,” said Mattison. “But not everything that is measured is actually managed. What is valued is managed.”

Currently, throughout the world, the price and scarcity of water are often disconnected. In Copenhagen, Denmark, water is priced at $7 per cubic meter (264 gallons), in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, it is only 3 cents. Such variances warp market incentives for water-intensive businesses where water may be cheap, even in regions with high risk of drought.

Mattison suggests that water should be valued similarly to the cost of capital, which would encourage businesses to make more pragmatic decisions, strengthening resource efficiency and making operations supply chains more resilient. This is why Ecolab partnered with Trucost to develop the Water Risk Monetizer, a tool to help businesses around the world better understand water risks in financial terms and the potential implications of water scarcity in their operating environment.

The Water Risk Monetizer provides actionable information to determine how water costs or scarcity may affect growth plans, providing a catalyst for better stewardship and impact. The web-based tool is also available at no cost to businesses throughout the world. The availability of tools like the Monetizer can help businesses factor water into decisions that support business growth while also protecting natural resources.

Innovative Partnerships Power Efficiencies in Water Management

In addition to incorporating water saving technologies into their plants like those used in Freeport, Texas, Dow explored how the water used within their plants could be better reused. Snehal Desai, Global Business Director for Water and Process Solutions at Dow, equates most of the world’s water systems to a one-way street. “You get water from a source, you treat it to a certain quality, you put it to whatever purpose it was serving, and then it goes out the other end.”

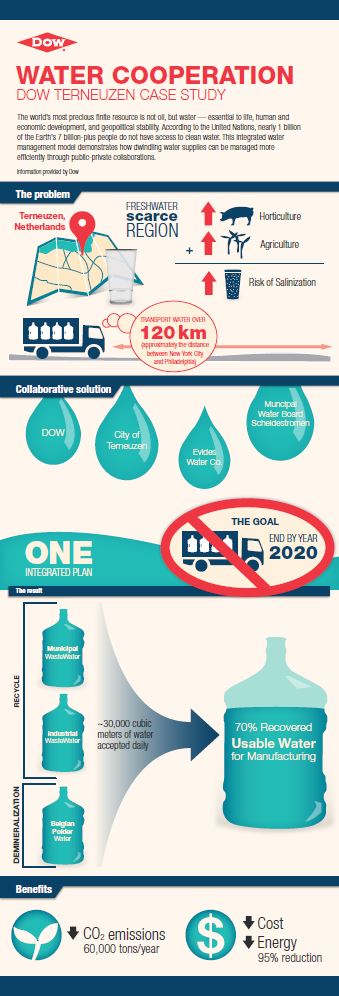

Recognizing that the energy demanded by such a process is significant, Dow entered into an innovative public-private partnership with the City of Terneuzen, the local water company, Evides, and the Water Board Scheldestromen, in order to reduce the company’s demand for fresh water. In the company’s largest chemical processing facility outside the United States in Terneuzen, a mid-sized city in the Netherlands, an innovative recycling system enables the site to process more than 2.6 million gallons of household wastewater every day, which is treated and then converted into high-pressure steam that is used within the plant. After the steam is used in production processes, the water is subsequently distilled and used in cooling towers where it will eventually evaporate into the atmosphere.

Recognizing that the energy demanded by such a process is significant, Dow entered into an innovative public-private partnership with the City of Terneuzen, the local water company, Evides, and the Water Board Scheldestromen, in order to reduce the company’s demand for fresh water. In the company’s largest chemical processing facility outside the United States in Terneuzen, a mid-sized city in the Netherlands, an innovative recycling system enables the site to process more than 2.6 million gallons of household wastewater every day, which is treated and then converted into high-pressure steam that is used within the plant. After the steam is used in production processes, the water is subsequently distilled and used in cooling towers where it will eventually evaporate into the atmosphere.

Previously, three million tons of water per year was discharged into the North Sea after just one use. The partnership has reduced the plant’s energy use by 95 percent when compared to the energy cost associated with the conventional alternative of desalination. “The amount of fresh water that we avoided taking out of the ground in the Netherlands left more for the community, more for agriculture, and more for what I like to call, a higher-order source,” said Desai.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for public-private partnerships, but successful partnerships like the one between Dow and the City of Terneuzen provide a framework that can be adapted to serve different local contexts. By looking outside their own four walls of manufacturing, Dow was able to both reduce their plants carbon emissions, and their demand on the community’s fresh water supply, in order to protect fresh water for use by future generations.

“The catalyst for this type of program is usually seen in communities where the situation is the most critical,” said Desai. “But I don’t think that means everyone else is off the hook.”

No one is off the hook. Waiting until a crisis to take action on critical challenges is no longer an option. Instead, quickly changing circumstances demand that corporate leaders consider the long-term impact of their actions in the context of the potential for short-term gain. In the realm of water conservation and energy production, such pay-offs only receive appropriate consideration when water is accurately valued and when the water-energy nexus is considered as a whole, rather than a sum of its parts.

Mattison called on one of America’s founding fathers to drive his point home. “Benjamin Franklin once said: ‘When the well runs dry, we shall know the value of water.’ I’d rather think that we should know the worth of water before the well runs dry.”

Once again, Net Impact has succeeded in raising the profile of a pressing social challenge that, if addressed correctly, can also deliver unimaginable returns. In the end, fortitude and foresight are required to make every drop count.

Feature photo: Chad Miller, CC BY 2.0

Melissa Mattoon

Melissa Mattoon is the Design and Publication Manager at the New Global Citizen where she seeks to showcase the impact of innovative leadership and global engagement around the world. She is also the Communications Coordinator at PYXERA Global.