In 2012, Xi Jingping, then Vice President of China, paid a return visit to the small town of Muscatine, Iowa. Xi reflected on his earlier visit, observing: “You were the first group of Americans I came into contact with. To me, you are America.” With these words to old friends, Xi marked his return to the community that had warmly welcomed him over a quarter century before.

In 1985, while a young bureaucrat from Iowa’s sister state, Hebei Province, Xi experienced a visit so personally meaningful that, 27 years later, he insisted on a return visit and a private reunion with the score of Muscatine residents to whom he had been closest. Xi’s reaction illustrates the power of citizen diplomacy, and the seriousness of the work entrusted to citizen diplomats, as do the reflections of his former Muscatine homestay hostess, Eleanor Dvorchak. She greeted Xi, in 2012, by recalling: “You were my first introduction to the Chinese people …. So many times you hear so much bad in the news. And after having met you, it was all washed away.” As Xi’s and Dvorchak’s observations underscore, citizen diplomats are their country for those with whom they connect.

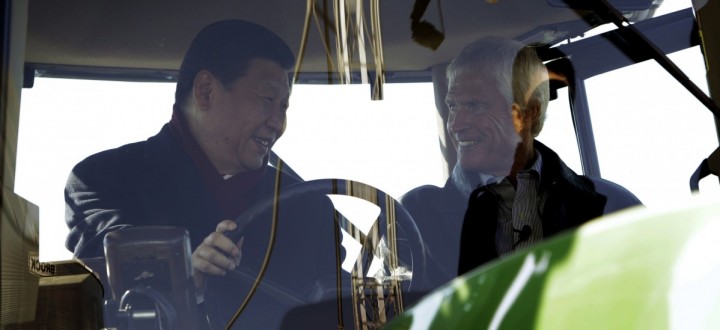

Xi Jingping, Vice President of China in 2012, during his visit to Hebei Province’s sister state, Iowa.

Thanks to his homestay experience, Xi Jingping, now the President of the People’s Republic of China, has a uniquely rich notion of the American people. He is only one of many high-government officials whose bilateral relations with America have been shaped by citizen exchange. At the height of the Cold War, Roswell Garst, an Iowa farmer and seed corn salesman, started a correspondence with Nikita Khrushchev that inspired a series of meetings aimed at improving Soviet farming practices. Khrushchev appreciated the straight-talking farmer, and when Garst eventually invited Khrushchev to his farm in central Iowa, the Soviet leader accepted. Indeed, Khrushchev insisted that his 1959 state visit to America include a tour of Garst’s farm and it became one of the highlights of Krushchev’s sojourn across the United States—the journey was otherwise largely characterized by tense interactions with government officials. Marking the 50th anniversary of his and his father’s visit to Iowa, Sergei Khrushchev observed to Rachel Garst, Roswell’s granddaughter:

“Your grandfather was one who made a hole in the Iron Curtain… He didn’t end the Cold War. He was the person who started the road to the end of the Cold War.”

These two examples demonstrate the heightened importance of citizen diplomacy when international relations are fraught. Khrushchev’s relationship with Roswell Garst and Xi Jingping’s relationship with Eleanor Dvorchak illustrate the ways in which people-to-people exchanges can transcend troubled government-to-government relations and inspire unlikely bonds of friendship and understanding. When Xi visited Muscatine in 1985, China and the United States were still emerging from decades of mutual recriminations, even armed conflict. Khrushchev visited Garst’s farm when a nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union still seemed possible.

The fruits of citizen diplomacy are mutual respect, understanding, and friendship across national boundaries. Today, these characteristics are notably lacking in U.S. relations with Iran, Pakistan, Syria, North Korea, Russia, and China. In some cases, the absence of citizen exchange has weakened bilateral ties to such an extent that formal diplomatic relations are all that remain, along with the accompanying increased risks of escalating tension and military engagement. It is on these frontiers of citizen diplomacy where individuals who embrace opportunities for citizen exchange have the ability to change the status quo for the better—as did Roswell Garst and the citizens of Muscatine.

People-to-people exchanges can transcend troubled government-to-government relations and inspire unlikely bonds of friendship and understanding.

Following in the footsteps of Garst and Xi’s Muscatine hosts, leaders in the American Mennonite faith community have, in recent years, embraced the opportunity to build bridges between the United States and Iran, by serving the Iranian people in the aftermath of a major earthquake. Following the Mennonites’ example, between March and June 2014, three delegations of faith leaders have visited the Islamic Republic of Iran, including Bishop Richard Pates of Des Moines, Iowa, Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, megachurch pastor Joel Hunter, and Robert Destro, professor of law at the Catholic University of America, as well as other American Catholics and Protestants, Mennonites, and Sunnis. They have met with senior Iranian religious officials to discuss topics ranging from confronting religious extremism to weapons of mass destruction.

In May, nine female Iranian seminarians from Jamiat al-Zahra, the world’s largest seminary for women, engaged in a citizen exchange with Eastern Mennonite University. In addition to being enrolled in the university’s Summer Peacebuilding Institute, the seminarians visited Washington, D.C. and an Amish community near Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Mohammad Shomali, the dean who accompanied the delegation, emphasized the importance of people-to-people relations, urging more American-Iranian exchange. “Nothing can replace face-to-face encounters as a path to peace,” said Shomali.

On yet another frontier of citizen diplomacy, faith leaders are seeking to improve relations between the United States and Pakistan. In May 2012, 24 faith leaders from Muslim, Jewish, and Christian backgrounds formed the U.S.-Pakistan Interreligious Consortium (UPIC) which has, since 2012, conducted four meetings in Lahore and Islamabad, Pakistan, and Muscat, Oman.

A herder milking his water buffalo for cream to serve with the tea he had prepared for the delegation, just outside Baddoke, a small town about 50 outside Lahore.

These meetings have included wide-ranging discussions of issues like blasphemy laws, free speech, American drone attacks, the troubled U.S.-Pakistani relationship, scripture, and religious tolerance. The visits to Pakistan allowed many Pakistani students their first interaction with a Jewish rabbi. The visits also yielded an inspired means of collectively addressing drone attacks, an issue that is troubling to nearly all Pakistanis. Adopting an approach that emphasizes the common values of all three faiths, the faith leaders have launched a joint U.S.-Pakistani campaign to raise money toward rebuilding the lives and communities where drone strikes occur.

Mumtaz Ahmad, one of the Pakistani members of UPIC, noted the way in which interactions with Americans have changed the Pakistanis’ view of the United States. Specifically, he noted his colleagues’ surprise at “the modesty and humility they saw in their American guests.”

“It was surprising for them for two reasons: they often find their own religious leaders here mostly stiff-necked and self-righteous,” he remarked. “They thought that all Americans speak like the U.S. officials who visit Pakistan”, who typically emphasize greater effort and good behavior.”

“Almost everyone told me that they saw a new face of America: deeply religious, caring, compassionate, humble, and willing to listen with respect and patience. You simply can’t imagine, my friends, how important was your trip to Pakistan!” said Ahmad. “It was for the first time that many of us came to know that ‘winning hearts and minds’ meant something real.”

Favorable contrasts, like Ahmad’s, between formal bilateral relations and people-to-people exchanges are not uncommon. The impact of citizen diplomacy is real and lasting and often helps individuals challenge and overcome persistent national stereotypes. Today, the accessibility of global travel, email, and social media offer people everywhere the opportunity to build meaningful global relationships. As a result, common folk, not government officials, represent their nations more and more to citizens of other countries. Those so engaged—citizen diplomats—now have the opportunity to shape international relations, even between nations at odds. Authentic, person-to-person contact is fundamental to meaningful international relations: the greater the number of such relationships, the greater the probability of correcting misunderstanding and enhancing cooperation.

Read this article in the print version

Authentic, person-to-person contact is fundamental to meaningful international relations.

The stories of Xi Jingping and Muscatine, and Roswell Garst and Nikita Khrushchev must inspire the citizen diplomacy community to first identify today’s frontiers of citizen diplomacy, and then deploy citizen diplomats to the troubled relationships found there, in the same spirit as the above-mentioned faith leaders from the United States, Iran, and Pakistan. As a proud Iowan, I am a true believer in the uniqueness of my state and its citizens, especially our skills as citizen diplomats. On a per capita basis, I believe Iowa packs more citizen diplomacy punch than any other state or province on our planet. But, I am willing to be proven wrong. I invite you to share stories of your state’s or province’s citizen diplomacy accomplishments, especially how you have found success on the “frontiers.” I hope you’ll take me up on that challenge so that we can learn from our parallel experiences. Work on the frontiers of citizen diplomacy is far too important to neglect.

Submit your stories to [email protected].

Chuck Montgomery

Chuck Montgomery, a Senior Managing Attorney for MidAmerican Energy Company (a Berkshire Hathaway company), has served as a board member for: V.O.I.C.E.S. (Hmong refugee resettlement), the Iowa Council for International Understanding, the U.S. Center for Citizen Diplomacy, and PYXERA Global. This service has fired Chuck’s passion for citizen diplomacy and led to involvement in projects like the Young Arab Business Fellows program, service on a State Department fact-finding mission to Iraq, ongoing service on the U.S.-Pakistan Leadership Forum, and advocacy for citizen diplomacy at the U.N.’s Alliance of Civilizations conference in Doha.

Chuck Montgomery has issued a timely challenge! He also articulately chronicled the central role of Iowans in stellar examples of citizen diplomacy. Since former Secretary of State Elihu Root wrote about popular diplomacy in the first ever issue of Foreign Affairs in September, 1922, many far-sighted Americans have recognized the vital role ordinary citizens can play in foreign relations. It is urgent that they do so in our tubulent world.