It was 4:30 in the afternoon and the Brazilian sun was already starting to set beyond the sleepy village of Trancoso. My husband and I, both weary from 20 hours of travel, could think only of a hot shower and a cool glass of water.

Instead, I stood before a persistently friendly Brazilian shopkeeper, trying to find our “chalet.” Though I have studied five different languages to varying degrees of proficiency, Portuguese was never one of them, a sad truth reflected in my ineffectual attempts to get where we were going.

“Hola!” “Bom dia!” After only ten hours in Brazil, I had successfully mastered the two most important phrases in Portuguese. Unfortunately, from there it could only get worse.

“Ingles?” I asked? He shook his head.

With nothing to lose, I made an attempt. Fusing a combination of French and Spanish modified words, and a few words I had seen on street signs, I hoped my new Brazilian friend might discern my meaning:

We are looking for Chalet Charmoso. “Os busca onde Chalet Charmoso,” I tried.

My message was a little distorted: The search where Chalet Charmoso, I said.

The shopkeeper smiled at my attempt to speak Portuguese, and then wrinkled his brow, puzzled.

“Chalet Charmoso? Eu não tenha ouvido falar dele,” he said, shaking his head.

Though I couldn’t understand a word, I clearly took his meaning: Chalet Charmoso was a place he had never heard of. He gestured at a nearby computer and encouraged me to Google it. Looking at the location page on Bookings.com, he quickly navigated to the photos, looking for a photo of the outside of the property. Once he had seen a photo of the front gate, he was certain of the direction we were headed.

Actively gesturing with his hands, he instructed me: “Vá sempre em frente. Em seguida, vire à direita. Em seguida, à esquerda. Em seguida, à direita novamente.”

Though in written form they looked quite different, I was delighted to learn that the words for right and left in Spanish and Portuguese had managed to maintain their phonetic point of origin: straight, then right, then left, then right again. The kind shopkeeper drew me a small map on the back of my receipt. We trundled off into the Brazilian sunset, map in hand.

The Words We Use

It has become a truism of humanitarian and social impact advocates that the words we use matter. When using terms or phrases that reflect the condescension, discrimination, or hatred of the past—even in jest—an individual can unintentionally undermine a person, practice, or institution. As an editor and communications professional, words are a medium that can be used or abused for good or ill.

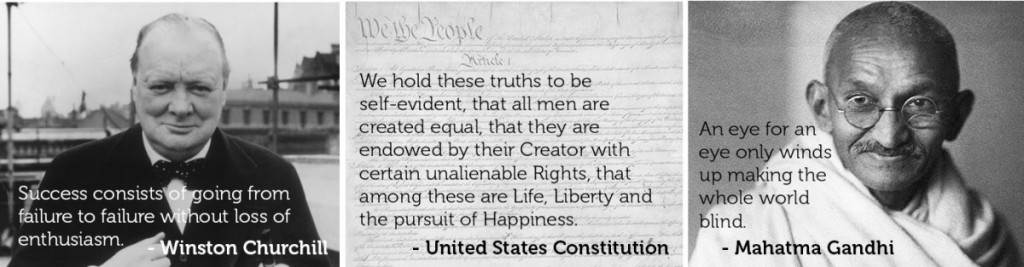

Across time, words have shaped revolutions, nations, and wars. When the events of the past have expired into memories or dates on a page in some underused textbook, the words of famous men and women remain.

Gandhi would be the first to advocate that the pen is mightier than the sword.

Staring down the smiling Brazilian shopkeeper, I was suddenly reminded of the opposite challenge: when we have no words, what do we do? I couldn’t remember the last time I had failed to be understood, much less left speechless. Suddenly, I realized how much I had taken for granted my ability to communicate, regardless of context.

Within this publication, a number of authors have touted the benefits of global mindset, of getting outside your comfort zone through an intimate interaction with another culture, whether through the immersion of global pro bono, or through citizen diplomacy and cultural exchange. Confronting a circumstance in which words have little effect has a number of unexpected (and largely positive) consequences. When talking doesn’t work, listening intently is often the next-best option. It is these lessons in listening that enable us to better understand one another in the future, making us better leaders, collaborators, and friends. The more we listen, the more we understand.

The Numbers of Nonverbal Communication

My conversation with the shopkeeper, though imperfect, was ultimately successful. Between our limited understandings of one another’s language, much hand-gesturing, significant patience, and our hand-drawn map we were able to arrive exactly where the shopkeeper intended us to go. Unfortunately, it turned out that the shopkeeper’s intuition about the location of the Chalet, based on the photograph of the gate, was incorrect. Our map, while an accurate reflection of the shopkeeper’s direction, did not bring us to our anticipated destination. While the interaction didn’t immediately result in us finding our way, we were still successful in communicating and understanding each other under problematic conditions.

In such circumstances, non-verbal communication becomes vital in a way it never was before. In truth, when interacting directly with another, words make up only a tiny piece of mutual understanding. Experts approximate that 55 percent of communication is body language, 38 percent of communication is dictated by vocal tone, and only seven percent is actually the words we use.

Turning around and driving back to town, we stopped to ask another friendly passerby. “Rua Dom Pedro?” I queried, now confident at least of the road we were looking for. Straight past the quadrado, right, left, and right were the next set of directions. Now going in the opposite direction, I ignored the fact that the directions were exactly the same as those we had previously received from the shopkeeper. Executing the directions left us at the bottom of a hill, at a T-junction, contemplating whether we had reached the last right, or if we had somehow taken a wrong turn. A man stood next to a gate nearby. We rolled down the window: “Rua Dom Pedro?” The man shook his head. “Rua Dom Pedro?” he muttered something undiscernible under his breath.

For my husband, this was the final straw. Frustrated that I had allowed us to get so far with nothing but a hand-drawn map, he turned the car around and headed back to the shop.

I once again found myself standing in front of the persistently friendly shopkeeper when I had an almost comical realization. Was there a phone number? The shop owner generously offered for me to use his computer to check my email. There, in my inbox, was one unread message from my host, Sandra. “Alicia, please call to let me know when you will arrive!” her phone number listed below the message.

A phone call returned a male British voice. Confused, I spoke cautiously: “Hello… is Sandra there?”

“This is John Carlo, her husband. You must be Alicia.” Never had my mother tongue brought such relief.

Words Are Resources, Too

Words—in any language—are a complex tool, which in the hands of humankind have allowed our species to innovate and advance in powerful ways. In gentlemen’s agreements and contracts alike, words are the foundation of collaboration, partnership, and mutual understanding. Words are an important resource for solving problems, enabling or disabling the efforts of future leaders seeking to develop adaptive solutions to persistent problems in resource-constrained environments. The absence of a common language, while its own resource constraint, forces creativity, resilience, and persistence to find a way.

My trip to Trancoso, under the pretext of a much needed vacation, turned out to be a much needed reminder of the raison d’ȇtre of this publication. Words, and the negotiations, conversations, and resulting social impact they facilitate, are powerful. Standing speechless on a Brazilian street corner, I felt nothing but gratitude for the gentle reminder.

Alicia Bonner Ness

Alicia Bonner Ness (@AliciaBNess) is the editor of the The New Global Citizen, where she seeks to showcase the impact of beneficiaries and implementers alike, empowering all those engaged in furthering social good to learn from one another. She is also the Communications Manager at PYXERA Global.

Insightful and well-written. I am saving for future use.

Pingback: 5 Books Aspiring Leaders Should Read This Summer - New Global Citizen