In The Locust Effect, Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros tackle one of the world’s darkest challenges, poverty and violence. Filled with startling new data and real-life accounts, The Locust Effect aims to uncover and end the unchecked violence that is undermining development for billions of the world’s poorest. Read the introduction below:

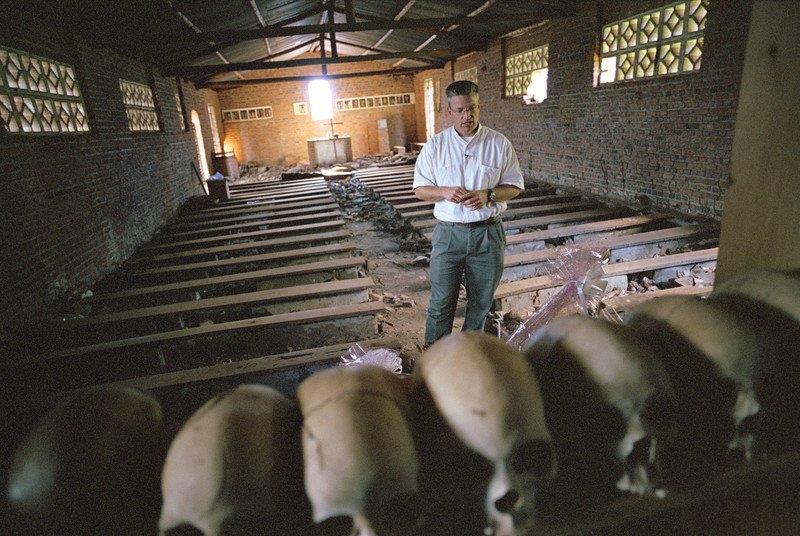

It was my first massacre site. Today the skulls are all neatly stacked on shelves, but when I first encountered them, they definitely were not. They were attached to bodies – mostly skeletal remains – in a massive mess of rotting human corpses in a small brick church in Rwanda. As the director of the tiny United Nations “Special Investigations Unit” in Rwanda immediately following the genocide in 1994, I was given a list of 100 mass graves and massacre sites across an impoverished, mountainous country where nearly a million people had been slaughtered – mostly by machete – in a span of about 10 weeks. When I stepped off the military transport plane to join the small international team of criminal investigators and prosecutors that were assembling in the Rwandan capital in the early weeks after the genocide, the country carried an eerie, post-apocalyptic emptiness. I didn’t even realize, until I was loading into a van outside the airport, that I had entered Rwanda without passing through customs and immigration – because there was no customs and immigration. The usual and powerfully subconscious markers of order and civilization – and security – had been utterly swept away in an engulfing orgy of genocidal war. And it didn’t feel good.

It was my first massacre site. Today the skulls are all neatly stacked on shelves, but when I first encountered them, they definitely were not. They were attached to bodies – mostly skeletal remains – in a massive mess of rotting human corpses in a small brick church in Rwanda. As the director of the tiny United Nations “Special Investigations Unit” in Rwanda immediately following the genocide in 1994, I was given a list of 100 mass graves and massacre sites across an impoverished, mountainous country where nearly a million people had been slaughtered – mostly by machete – in a span of about 10 weeks. When I stepped off the military transport plane to join the small international team of criminal investigators and prosecutors that were assembling in the Rwandan capital in the early weeks after the genocide, the country carried an eerie, post-apocalyptic emptiness. I didn’t even realize, until I was loading into a van outside the airport, that I had entered Rwanda without passing through customs and immigration – because there was no customs and immigration. The usual and powerfully subconscious markers of order and civilization – and security – had been utterly swept away in an engulfing orgy of genocidal war. And it didn’t feel good.

In those early days, my task was to help the UN’s Commission of Experts make a gross accounting of what had taken place and to begin gathering the evidence against the leaders of the genocide (it would be more than a year before any international tribunal would be set up). But with hundreds of thousands of murders, where were we to start?

We ended up starting in Ntarama, a small town south of Kigali, and in a small church compound where all the bodies remained just as their killers had left them – strewn wall to wall in a knee-high mass of corpses, rotting clothes and the desperate personal effects of very poor people hoping to survive a siege.

But they did not survive.

And now four Spanish forensic experts were working with me in picking through the remains and lifting out each skull for a simple accounting: “Woman - machete. Woman - machete. Child - machete. Woman - machete. Child - machete. Child - blunt trauma. Man - machete. Woman – machete …” On and on it went for hours.

Gary Haugen visits Ntarama Church, a Rwanda genocide site in 2006.

Our task was to assemble from survivor testimony and the horrible mess of physical evidence a very precise picture of how mass murder actually happens. And over time, the question began to take a fierce hold on me. I couldn’t stop trying to picture it in my mind. What is it like, exactly, to be pressed up against the back wall of this church with panic on every side from your terrified family as the steel, blood-soaked machetes hack their way to you through your screaming and slaughtered neighbors?

What eventually emerged for me, and changed me, was a point of simple clarity about the nature of violence and the poor. What was so clear to me was the way these very impoverished Rwandans at their point of most desperate need huddled against those advancing machetes in that church did not need someone to bring them a sermon, or food, or a doctor, or a teacher, or a micro-loan. They needed someone to restrain the hand with the machete – and nothing else would do.

None of the other things that people of good will had sought to share with these impoverished Rwandans over the years was going to matter if those good people could not stop the machetes from hacking them to death. Moreover, none of those good things (the food, the medicine, the education, the shelter, the fresh water, the micro-loan) was going to stop the hacking machetes. The locusts of predatory violence had descended – and they would lay waste to all that the vulnerable poor had otherwise struggled to scrape together to secure their lives. Indeed, not only would the locusts be undeterred by the poor’s efforts to make a living, they would be fattened and empowered by the plunder.

Just as shocking to me, however, was what I found following the Rwanda genocide as I spent the next two decades in and out of the poorest communities in the developing world: a silent catastrophe of violence quietly destroying the lives of billions of poor people, well beyond the headlines of episodic mass atrocities and genocide in our world.

Without the world noticing, the locusts of common, criminal violence are right now ravaging the lives and dreams of billions of our poorest neighbors. We have come to call the unique pestilence of violence and the punishing impact it has on efforts to lift the global poor out of poverty the locust effect. This plague of predatory violence is different from other problems facing the poor; and so, the remedy to the locust effect must also be different. In the lives of the poor, violence has the power to destroy everything – and is unstopped by our other responses to their poverty. This makes sense because it can also be said of other acute needs of the poor. Severe hunger and disease can also destroy everything for a poor person – and the things that stop hunger don’t necessarily stop disease, and the things that stop disease don’t necessarily address hunger. The difference is the world knows that poor people suffer from hunger and disease – and the world gets busy trying to meet those needs.

But, the world overwhelmingly does not know that endemic to being poor is a vulnerability to violence, or the way violence is, right now, catastrophically crushing the global poor. As a result, the world is not getting busy trying to stop it. And, in a perfect tragedy, the failure to address that violence is actually devastating much of the other things good people are seeking to do to assist them.

For reasons that are fairly obvious, if you are reading this book, I’m pretty sure you are not among the very poor in our world – the billions of people who are trying to live off a few dollars a day. As a result, I also know that you are probably not chronically hungry, you are not likely to die of a perfectly treatable disease, you have reasonable access to fresh water, you are literate, and you have reasonable shelter over your head. But there is something else I know about you. I bet you pass your days in reasonable safety from violence. You are probably not regularly being threatened with being enslaved, imprisoned, beaten, raped, or robbed.

But if you were among the world’s poorest billions, you would be. That is what the world does not understand about the global poor – and that is what this book is about. Together, we will make the difficult journey into the vast, hidden underworld of violence where the common poor pass their days out of sight from the rest of us. My colleagues at International Justice Mission (IJM) spend all their days walking through this subterranean reality with the poorest neighbors in their own communities in the developing world; in this volume, their intimate stories allow the data and statistical reality to take on flesh and a human heart that matters to us.

IJM is an international human rights agency that supports the world’s largest corps of local, indigenous advocates providing direct service to impoverished victims of violent abuse and oppression in the developing world. In poor communities in Africa, Latin America, South Asia and Southeast Asia, IJM supports teams of local lawyers, investigators, social workers and community activists who work full-time to help poor neighbors who have been enslaved, imprisoned, beaten, sexually assaulted, or thrown off their land. These teams work with local authorities to rescue the victims from the abuse and to bring the perpetrators to justice – and then they work with local social service partners to walk with the survivors on the long road to healing, restoration and resilience for the long haul. And after thousands of individual cases, their stories have brought a different reality of poverty to the surface.

When we think of global poverty we readily think of hunger, disease, homelessness, illiteracy, dirty water, and a lack of education, but very few of us immediately think of the global poor’s chronic vulnerability to violence – the massive epidemic of sexual violence, forced labor, illegal detention, land theft, assault, police abuse and oppression that lies hidden underneath the more visible deprivations of the poor.

Indeed, I am not even speaking of the large-scale spasmodic events of violence like the Rwandan genocide, or wars and civil conflicts which occasionally engulf the poor and generate headlines. Rather, I am speaking of the reality my IJM colleagues introduced to me in the years that followed my time in Rwanda – the reality of common, criminal violence in otherwise stable developing countries that afflicts far more of the global poor on a much larger and more persistent scale – and consistently frustrates and blocks their climb out of poverty.

But we simply do not think of poverty this way – even among the experts. Perhaps the highest profile statement of the world’s most fundamental priorities for addressing global poverty were set forth by the UN in its Millennium Development Goals – eight economic development goals endorsed by 193 nations at the UN’s Millennium Summit in 2000 as the framework for galvanizing the world to attack global poverty. And yet, in that monumental document, addressing the problem of violence against the poor is not even mentioned.

This is particularly tragic because, as we shall see, the data is now emerging to confirm the common-sense understanding that violence has a devastating impact on a poor person’s struggle out of poverty, seriously undermines economic development in poor countries, and directly reduces the effectiveness of poverty alleviation efforts. It turns out that you can provide all manner of goods and services to the poor, as good people have been doing for decades, but if you are not restraining the bullies in the community from violence and theft – as we have been failing to do for decades – then we are going to find the outcomes of our efforts quite disappointing.

This is not to say, of course, that poverty alleviation efforts haven’t met with some impressive results—especially in reducing the most extreme forms of poverty, i.e. those who live off $1.25 a day. But as we shall see, the number of people forced to live off $2.00 a day (more than 2 billion) has barely budged in thirty years, and the studies are now accumulating the make a nexus to common violence undeniable. No one will find in this volume any argument for reducing our traditional efforts to fight poverty. On the contrary, billions still mired in fierce poverty cry out for us to redouble our best efforts. But one will find in these pages an urgent call to make sure that we are safeguarding the fruits of those efforts from being laid waste by the locusts of predatory violence.

In fact, as you encounter these intimate stories of how common poor people are relentlessly ambushed by violence in the developing world, have an eye for the brutal real-life implications of these terrifying events for the individuals who endure them – the productive capabilities lost, the earning potential stolen, the confidence and well-being devastated by trauma, the resources ripped away from those on the edge of survival and poured instead into the pockets of predators. Then, as you consider the statistical data that multiplies these devastating individual tragedies by the millions across the developing world, you will sense the scandalous implications of this failure to address the massive sinkhole of violence that is swallowing up the hope of the poor.

But perhaps even more surprising than the failure to prioritize the problem of violence against the poor is the way that those who do appreciate the problem ignore the most basic solution – and the solution they rely upon most in their own communities: law enforcement. As we shall see together, the poor in the developing world endure such extraordinary levels of violence because they live in a state of de facto lawlessness. That is to say, basic law enforcement systems in the developing world are so broken that global studies now confirm that most poor people live outside the protection of law. Indeed, the justice systems in the developing world make the poor poorer and less secure. It’s as if the world woke up to find that hospitals in the developing world actually made poor people sicker – or the water systems actually contaminated the drinking water of the poor.

One would hope that if the world woke up to such a reality, it would swiftly acknowledge and respond to the disaster – but tragically, the world has neither woken up to the reality nor responded in a way that offers meaningful hope for the poor. It has mostly said and done nothing. And as we shall see, the failure to respond to such a basic need – to prioritize criminal justice systems that can protect poor people from common violence – has had a devastating impact on two great struggles that made heroic progress in the last century but have stalled out for the poorest in the twenty-first century: namely, the struggle to end severe poverty and the fight to secure the most basic human rights.

Indeed, for the global poor in this century, there is no higher-priority need with deeper and broader implications than the provision of basic justice systems that can protect them from the devastating ruin of common violence. Because as anyone who has tasted it knows, if you are not safe, nothing else matters.

The Locust Effect then is the surprising story of how a plague of lawless violence is destroying two dreams that the world deeply cherishes: the dream to end global poverty and to secure the most fundamental human rights for the poor. But the book also reveals several surprising stories about why basic justice systems in the developing world came to be so dysfunctional. It turns out that when the colonial powers left the developing world a half a century ago, many of the laws changed but the law enforcement systems did not – systems that were never designed to protect the common people from violence but to protect the regime from the common people. These systems, it turns out, were never re-engineered.

Secondly, given the brokenness of the public justice system, forces of wealth and power in the developing world have carried out one of the most fundamental and unremarked social revolutions of the modern era in building a completely parallel system of private justice, with private security forces and alternative dispute resolution systems that leave the poor stuck with useless public systems that are only getting worse.

Finally, for surprising historical reasons (and tragic effect), the great agencies of poverty alleviation, economic development, and human rights have purposely avoided participating in the strengthening of law enforcement systems in the developing world.

From a realistic confrontation with the challenge, The Locust Effect pivots toward the great hope for change that comes from history and current projects of transformation quietly going forth in the world. It turns out that just about every reasonably functioning public justice system in the world today was, at one time in history, utterly dysfunctional, corrupt and abusive. The Locust Effect seeks to recover the lost and inspiring story of how, in relatively recent history, justice systems were transformed to provide reasonable protection for even their weakest citizens. Moreover, great signs of hope are profiled in a variety of demonstration projects being carried out by IJM and other agencies around the world that demonstrate it is possible to transform broken public justice systems in the developing world so they effectively protect the poor from violence.

To secure meaningful hope, however, we must be standing on the solid rock of reality. A breezy wishful thinking that has not seriously confronted the depth of the problem will not do. Before the world could begin to turn the corner on the AIDS epidemic, as it has now begun to do, millions of perfectly healthy people around the world had to stomach an honest look at what was happening to millions of other people in the world who were dying in the most horrific ways on an apocalyptic scale. From that brave refusal to look away – a decision made by millions of common people around the globe who could have turned the page, changed the channel, or clicked away – a hope grounded on hard reality was found, and a steady march out of the darkness has begun.

Likewise, a better day for the poorest in our world will only come as we are willing to walk with them into the secret terror than lies beneath the surface of their poverty. Accordingly, we would ask you to decide to persevere through these first chapters as they take you, with some authentic trauma, through that darkness – because there is real hope on the other side. Later, not only will we discover together a fresh and tangible reminder from history of how diverse developing societies reversed spirals of chaotic violence and established levels of safety and order once considered unimaginable, but we will also explore a number of concrete examples of real hope emerging today, including projects from IJM, other non-governmental organizations and government agencies, that have measurably reduced the poor’s vulnerability to some of the worst forms of violence – including sex trafficking, slavery, sexual abuse, torture, and illegal detention.

…

This volume is simply the story of that long journey of terrible discovery from the piled carnage inside the church in Ntarama to the deeply hidden plague of everyday violence that is the terror of global poverty in our day. In either case, the challenge is to see violence for what it is and to end the impunity that allows it to happen again. In Ntarama, the remains we pulled out in 1994 are all neatly stacked on shelves in a genocide memorial now constructed at the site. If the stark reminder of what we are capable of doing to each other, and what we are capable of failing to do for each other provokes to action the better – and more courageous – angels of our nature, that would be a worthy memorial.

Reprinted from The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence by Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros with permission from Oxford University Press USA, © International Justice Mission 2014.

New Global Citizen

The New Global Citizen chronicles the stories, strategies, and impact of innovative leadership and international engagement around the world. This is the world of the new global citizen. This is your world.