Augustina Mejiasamata, a 34-year- old Quechua woman who lives in an Andes mountain village two hours outside of Cusco, Peru, had already waited in line for almost an hour to receive her free Pap smear and breast exam.

Augustina Mejiasamata, a 34-year- old Quechua woman who lives in an Andes mountain village two hours outside of Cusco, Peru, had already waited in line for almost an hour to receive her free Pap smear and breast exam.

“Por qué vino Ud. a la clinica hoy?” Why did you come to the clinic today? I asked.

The president of her village, she explained, had distributed pamphlets a few days earlier, announcing to the women of the village that a free clinic was taking place. She explained her reasons for coming.

“Para saber si estoy mal o no,”—to know if I am sick or not. She clarified further: “Y si tengo este papanicolauu…”—and if I have Papanicolaou, mistaking the name of the test for the name of the disease.

Augustina Mejiasamata, a 34-year-old Quechua woman, receives a free cervical cancer screening and breast exam outside Cusco, Peru.

Augustina was one of close to 300 women who attended a four-hour outreach clinic in Ancahuasi, Peru, offered by CerviCusco, a clinic in Cusco, founded in 2007 by Dr. Daron Ferris, an expert gynecological oncologist at Georgia Regents University. Dr. Ferris and his staff seek to provide cervical cancer screening and treatment to the women of the rural Andes Mountains. They frequently conduct extensive outreach campaigns to rural towns and villages outside the city of Cusco, where women from the surrounding area can receive a free test at their local community clinic.

Most women, await the cervical cancer test—Papanicolaou, in English abbreviated to ‘Pap’—diligently wait in line for hours at the clinic to make sure they don’t have “algo malo“—something bad—but don’t understand exactly what they’re being tested for. After a rapid Pap test and breast exam, patients receive a bright yellow slip of paper, instructing them to return to the clinic in one month’s time to retrieve their results. Though attrition rates are high, those with abnormalities who do return for their results are referred back to the clinic in Cusco for treatment.

Cervical Cancer: An Objective Marker for Health Disparity

According to the World Health Organization, cancer of the cervix is the second-most common cancer among women worldwide. Nearly 500,000 women are diagnosed and over 250,000 die from the disease every year because they lack access to timely screening and prevention services. In Peru, cervical cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths among women. The cervix is a one-inch-wide cylindrical muscle that joins a woman’s uterus to her vagina. It plays a critical role in all aspects of a woman’s reproductive cycle, including enabling sperm to fertilize the ovum, keeping in vitro babies within the uterus, and allowing the flow of menstruation.

“Cervical cancer is an entirely preventable and curable disease that, with the right resources, could be eliminated worldwide.”

It was during my visit to CerviCusco that I learned that cervical cancer is an entirely preventable and curable disease that, with the right resources, could be eliminated worldwide. Early-stage cervical cancer can be diagnosed and treated in a number of ways; only in its final stages does it become deadly. Cervical cancer is caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV), a very common and asymptomatic sexually transmitted disease. Most people on earth will contract HPV at some point in their lives, but with a healthy immune system, most can successfully fight and clear the infection without ever knowing they were ill to begin with. Even if cancer does develop, if diagnosed early enough, it is still easily treatable with cryotherapy or surgery. Yet, scaling a developed-market approach to screening and treating cervical cancer is unlikely to provide an effective pathway to eliminating the disease worldwide. Doing so will require faster and more affordable screening and treatment, as well as effective data management to ensure that screening and treatment targets are being met.

Dr. Erin Kobetz, Senior Associate Dean of Health Disparities at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, believes that cervical cancer is an objective marker for health disparity. “If all women had access to screening,” she says, “there would be no cervical cancer.” In other words, women who die because of the disease are almost always those who lack access to timely and affordable healthcare.

Extensive research has been done to develop cervical cancer prevention methods. Thanks to both Merck and GSK, women and girls between ages 11 and 26 with access to affordable healthcare can be immunized against the most virulent (cancer causing) strains of HPV. But at about $130 a dose, these vaccines are not accessible to millions of women around the world.

Innovating on Point of Care Diagnosis

While the traditional approach to screening and treatment has reduced cervical cancer’s morbidity in the United States by more than 50 percent over the last 30 years, Dr. Kobetz believes a point-of-care HPV test could present a more effective means of diagnosis. Requiring multiple trips to the clinic simply to receive a definitive diagnosis raises the risk of patient attrition, which can delay treatment and lead to death.

Over the past 11 years, Dr. Kobetz has been testing a different approach through her work with Patne en Aksyon (Partners in Action), a campus-community partnership designed to reduce the excess disability and death from breast and cervical cancer among Haitian women in south Florida, who like the women of Peru, have an unusually high prevalence of cervical cancer, developing the disease at four times the rate of the average woman in the United States.

Early on, Dr. Kobetz learned that many Haitian women practice vaginal hygiene in a manner that weakens the body’s natural immune response to the virus. She also encountered significant cultural barriers that lead women who fear the death sentence of a cancer diagnosis to avoid screening altogether. Based on their successful community outreach program in Little Haiti, Dr. Kobetz and her team have developed a point-of-care HPV test that allows a woman to self-sample her cervix, and a community health worker to use a solution-based test to determine whether she has HPV. The test is still in clinical trials, but once approved, should be as easy to buy and use as a pregnancy test.

Scaling the See-and-Treat Approach

Jhpiego, a global health affiliate of Johns Hopkins University, is also seeking to eliminate cervical cancer through a single-visit approach to cervical cancer prevention, the “see-and-treat” approach, which is becoming mainstream. In traditional treatment protocol, a woman with an abnormal Pap smear result will receive a colposcopy exam, visualizing abnormal lesions with the application of acid, which are then biopsied and later surgically removed.

Instead of first performing a Pap smear, requiring a woman to wait up to a month for the results, the single-visit approach cuts straight to the colposcopy. On the first visit, a clinician uses acid to diagnose the cervix, and immediately treats abnormal lesions with cryotherapy, painlessly applying CO2 to freeze (and remove) abnormal cervical lesions that could develop into cancer. The approach is now standard cancer prevention protocol in more than six countries, and can be performed by certified nurses or mid-level clinicians, freeing up surgeons to perform more complex procedures.

To improve on the delivery of this approach, Jhpiego and the Johns Hopkins Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design have developed an even more efficient cryotherapy device. CryoPop is a low-cost, sustainable, portable cryotherapy device that uses dry ice to treat pre-cancerous cervical lesions. The award-winning innovation relies only on compressed CO2, which is 10 times cheaper and 30 times more efficient than other cryotherapy devices.

Tracking Effective Diagnosis and Care

In some areas of the world, women are being effectively screened for cervical cancer, but health Ministries often lack the data management infrastructure needed to effectively report on their progress combating the disease. In Kenya, for example, though the see-and-treat approach advocated by Jhpiego is a standard treatment protocol, data is manually captured at facilities, it is often not reported in the country’s health database, and is therefore unavailable at district and national levels. As a result, it is almost impossible to measure and monitor screenings and treatment activities across the country. Additionally, data collection procedures are not standardized across facilities, and until recently, the District Health Information System did not include any cervical cancer related indicators.

In 2012, a team from IBM’s Corporate Service Corps worked with PEPFAR and Kenya’s Ministry of Health (MOH) to identify issue areas and make recommendations for improved data tracking across the country. The IBM team’s roadmap took a systematic approach, outlining how the MOH could leverage the existing HIV care and treatment network to refer patients for cervical cancer testing. Additionally, the recommendations included an approach for standardizing data recording and training on cervical cancer screening, treatment, and data capture methodologies.

Three years later, Kenya’s MOH is still hoping to utilize IBM’s recommendations but has failed to implement much of the program because of a realignment of priorities within PEPFAR that shifted funding away from cervical cancer.

Aligning Resources to Meet the Need

With alternative testing and treatment options available, traditional protocol—a Pap smear and mandatory follow-up visit—is no longer the only way to effectively fight the disease. Yet, resources are needed to further these different points of impact. Funding from the GE Foundation has provided critical support for Dr. Kobetz’s research in HPV testing, and to the Johns Hopkins Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design in its efforts to develop innovative medical devices, including CryoPop.

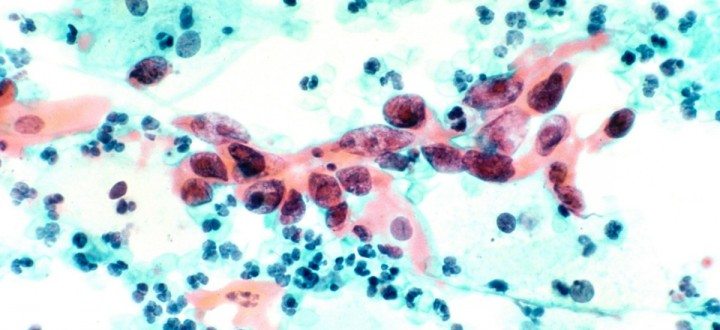

A cytologist inspects Pap smear pathology slides at the CerviCusco clinic.

Likewise, many institutions lack access to the kind of talent they need to operate effectively. Corporate volunteers have played a key role in advancing a number of cervical cancer interventions. Though progress has been slower than hoped, the IBM Corporate Service Corps’ support for Kenya’s Ministry of Health played a pivotal role in helping the country advance its position on cervical cancer monitoring. A team of employees from IBM and Becton Dickson (BD), worked with CerviCusco in 2012 to improve the organization’s electronic records management system, and to support the organization’s business development efforts. According to James Walker, one of the BD employees who worked on CerviCusco’s business development plan, “This much needed increase in funding will enable CerviCusco to reach an additional 35,000 women over the next three years.”

But the commitments of GE, BD, and IBM are not enough to eradicate this unnecessarily deadly disease. The Sustainable Development Goals call on the development community to reduce by one-third pre-mature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and to provide access to vaccines. Improving diagnostics, expanding access to innovative treatment tools, and better monitoring the fight against the disease are all extremely effective ways to advance this goal. With the right funding and implementing partners, cervical cancer could be eliminated worldwide.

Alicia Bonner Ness

Alicia Bonner Ness (@AliciaBNess) is the editor of the The New Global Citizen, where she seeks to showcase the impact of beneficiaries and implementers alike, empowering all those engaged in furthering social good to learn from one another. She is also the Communications Manager at PYXERA Global.