It all started with a toilet—this one to be specific. That, and a desperate craving for adventure.

The first time that I saw this life-changing montage of toilets was in 2007. I stood deep in the heart of the Peruvian Amazon, as far as I had yet been from the comfort of familiarity, gazing out across the river at thousands of floating shacks. I had been looking for a little adventure and as a student of international business, I elected for a study abroad tour of Latin America. I envisioned delectable samplings of Mexican flavor, awe-inspiring moments while exploring the ruins of ancient cultures, gorgeous landscapes (and beaches!), good rum, and energizing Latino beats blasted from night clubs that pulsed on until the sun came up. I found those things.

The first time that I saw this life-changing montage of toilets was in 2007. I stood deep in the heart of the Peruvian Amazon, as far as I had yet been from the comfort of familiarity, gazing out across the river at thousands of floating shacks. I had been looking for a little adventure and as a student of international business, I elected for a study abroad tour of Latin America. I envisioned delectable samplings of Mexican flavor, awe-inspiring moments while exploring the ruins of ancient cultures, gorgeous landscapes (and beaches!), good rum, and energizing Latino beats blasted from night clubs that pulsed on until the sun came up. I found those things.

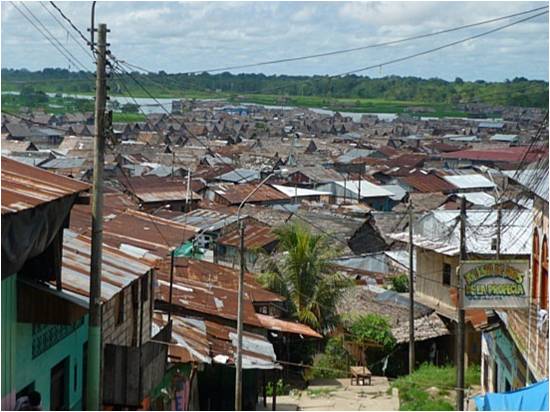

And I found something else, something less expected. It was called ‘Floating Belen’, nicknamed the Venice of Peru, but often described (and more accurately so) as the Horror of Peru. I saw two to three families subsisting in a single, one-roomed, floating shanty. Numerous children looked out from each home half-naked and wearing dirty, torn clothing—revealing bulging bellies that signaled the affliction of parasites and malnutrition. With little access to clean water, they used the river to swim, play, wash their clothes, brush their teeth, and bath. They also used it as a toilet. I found this to be generally unthinkable, and even more so because the situation seemed to be largely devoid of solutions. Without really knowing what else to do, I agonized over the devastating living conditions, the poor health and hygiene, and the pitiable futures of the residents of this community, and especially their children. It was a problem of access, and a lack thereof.

Originally, I had opted to study abroad in various parts of Latin America to supplement my Spanish degree with immersion in different dialects and to prepare myself for an international business career in this region. But after visiting this part of Peru, I began to question my pursuit of an education in business. I wished I had the foresight to focus my studies on becoming a doctor or an engineer so I could do something about this mess.

While I could not relate directly with this level of poverty, I did have a unique connection with these people. I had come from a very low-income family and that came along with a very important life lesson—you have to work twice as hard, have triple the ambition, and quadruple the perseverance to succeed. Every day, I am grateful that my efforts were rewarded with a university scholarship that gave me the opportunity to change my own life and invent my own future. When I visited this impoverished community, what I saw were hardworking, capable, and creative people that were held in captivity by their lack of access to the resources and opportunities they needed for development. I looked at these people and saw something of myself—only, they did not have access to a scholarship; they did not have access to much of anything. I wanted to change that, to find a way to use my background in business to help them access what they needed to steer their own development.

But life was calling me back home to my accounting classes and I was soon engaged in an internship in international tax consulting, working to maximize tax benefits of large multi-nationals. While the work was fascinating, I found myself uninspired by the task of helping the rich get richer. Rather, my interests gravitated back towards using my business training to improve situations like those I had seen in Peru.

So, after successfully finishing my internship, I set out to discover more of the world. As I was backpacking through countries like Nicaragua, Cambodia, and Vietnam, I saw, again and again, reflections of the same debilitating poverty I had first witnessed in Peru. I felt that these people deserved more than charity; they deserved a chance to help themselves— the same chance I had once been given. With these new interests and experiences at hand, I began to study business in a different light—business as a tool for fighting poverty. I became most interested in a new business paradigm, coined ‘social business’, introduced by Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize for his work as a pioneer of microfinance.

Social business drives opportunity by delivering sustainable social value. Profitability is also key but, only as a means of achieving financial sustainability within the business and expanding its social benefit. I suddenly realized that I did not need to be a doctor or an engineer to make a difference—I already had valuable business skills that could be applied to increase access to resources and spur social and economic growth within impoverished communities.

Since that initial, life-altering moment in Peru, I have been working with this concept of ‘social business’ in the fields of sanitation, hygiene, and food security. My professional objective is to re-imagine traditional business models, not simply to include the poor in western models, but rather to innovate creative, appropriate, and accessible solutions specific to the unique situations found within impoverished communities—solutions that are environmentally and socially sustainable as well as economically viable. I believe that there is a great opportunity to create shared value simply by leveraging business in innovative ways. By doing so, we can offer the poor an opportunity to get what they need, in a dignified and sustainable manner—just like the rest of us are able to do. ‘Business as usual’ hasn’t been good enough for a long time—it’s time to do business with people in mind.

The most exciting part is that, increasingly, we have the tools necessary to carry out such a mission. MBAs Without Borders (MWB), for example, is a program that recognizes and promotes the possibilities of creating sustainable solutions through the application of business principles. I am elated to have the opportunity to be an MWB Advisor on the ground with a fair-trade organization like Kara Weaves whose business respects people and the environment while seeking to preserve cultural heritage. As I spend the next five months in India, I’ll be engaged in the process of co-generating a creative vision and a sustainable model that can touch lives and create opportunities. The challenge for the future will be how to scale and mainstream these types of social enterprises to achieve global impact. Challenge accepted!

Jessica Custer

Jessica Custer is an MBAs Without Borders advisor currently serving Kara Weaves, a fair-trade organization that works to sustain local, traditional hand-weaving cultures in Kerala, India. With her MSc in Sustainable Development from HEC Paris, Jessica seeks to aid in the development of socially and environmentally sustainable business models that improve access to critical resources for impoverished populations in emerging markets, thereby empowering individuals to improve their own lives.

Muy buen articulo Jessica, describes claramente la realidad de la sociedad de Iquitos, ademas que reafirmas tu compromiso por mejorar la calidad de vida de las personas que no tienen esa oportunidad. Tengo el honor de haber compartido ideas y proyectos para ayudar en algo a esta sociedad, ademas como peruano y amigo te felicito por este innovador trabajo que vienes haciendo, estoy seguro que lo harás muy bien, y pronto estaremos compartiendo nuevos proyectos para mejorar nuestro mundo. Éxitos Jessica, te lo mereces.