This is part two in a three part Citizen Diplomacy series highlighting how cross-border experiences shape individuals and their communities. Read part one here. Read part three here.

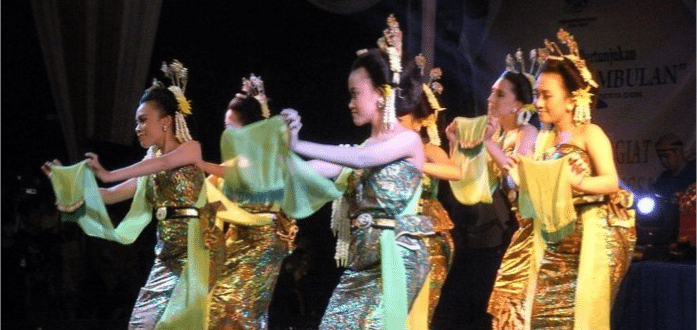

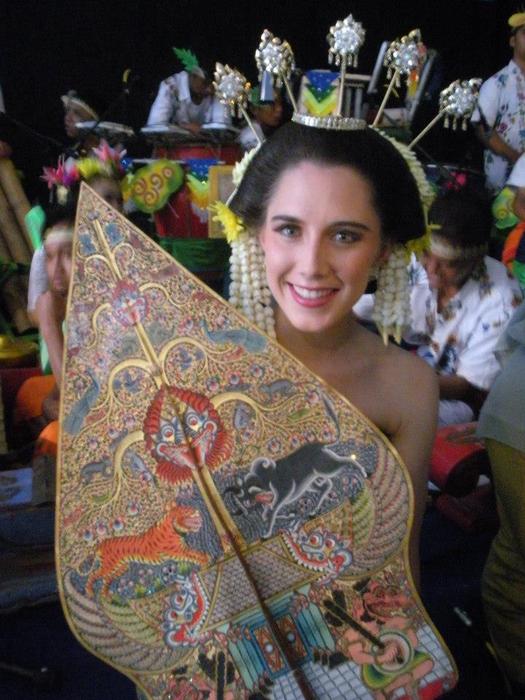

I breathe in the delicate aroma of jasmine from the flower garlands dangling from my hair and neck. My head feels heavy, thanks to the headpiece pinned securely in place—it must weigh ten pounds. My scalp aches from the stabbing pins, but I don’t pay much attention. I’m too busy trying to avoid tripping in my tightly wrapped batik skirt. When the gamelan musicians strike their first notes, I shuffle on stage with the other dancers and begin to dance with my knees slightly bent and my wrists sharply angled as they grasp my scarf. I hope that my height and brown hair don’t make me stick out too discordantly.

When I first imagined my job responsibilities as a Fulbright English Teaching Assistant (ETA) in Indonesia, performing gambyong (a courtly Javanese dance) at a public, Indonesian celebration was certainly not on my list. Before I arrived in 2012, I hadn’t anticipated that my “work” would encompass everything from teaching English class to spending my free time in dance class with students or attending weddings and funerals with fellow teachers.

Each year, the Department of State sends 1,900 Americans on an international exchange as part of the Fulbright U.S. Student program. The initiative provides an opportunity for educators, students, and academics to teach, learn, or research in more than 140 countries. The ETA program in Indonesia is specifically targeted for recent college graduates and young professionals to teach English in public and private secondary schools for ten months. A country comprised of more than 17,000 islands, I chose to work in Indonesia because of its linguistic, cultural, and religious diversity.

I left for Madiun prepared to engage with my community as a teacher, expecting to spend hours planning lessons, grading quizzes, and tutoring students. I quickly found out that I was wrong.

My ETA cohort and I arrived during a time of Indonesian resistance to foreign workers, when getting a visa for anything other than academic purposes required traversing excessive and lengthy bureaucratic processes. Even as other ASEAN countries prepared to increase trade and cross-employment in the region, Indonesia increasingly retreated from integration. While most ETAs are encouraged to take on additional volunteer or research projects, our scope in Indonesia was particularly limited due to the visa restrictions. We were never formally “teachers” at all, but rather “co-teachers,” warned that officials might check up on us at school and that we must always attend class with the senior teacher by our side. Due to the cultural realities of this dynamic, effective co-teaching rarely occurred. Our Commission advised us to seek informal opportunities to engage outside the classroom. Suddenly, my definition of “work” expanded.

My role was no longer to be a teacher, but to be a friend, writer, counselor, trainer, athlete, expert, insider, outsider, vocal coach, judge, translator, editor, photographer, and even gambyong performer. With this new direction, I let myself immerse in the goings-on of my community without feeling like I was neglecting “work” – ETAs in other countries may have worried about designing a rigorous research project or putting in enough volunteer time in their brief ten months, while I was able to regularly have dinner with my host family, learn competitive badminton with a group of teachers, and record a CD with my students. This was work, and it was meaningful.

I was also an American cultural ambassador. I was “on” 24 hours a day, every interaction an opportunity to either represent my culture well or perpetuate misunderstanding. Over time, my daily interactions with Indonesians helped us understand each other better, and navigate moments of conflict. For example, for many Indonesian girls it is inappropriate to be outside of the home past Maghrib (the fourth of the five daily Muslim prayers) and this societal expectation was extended to me as an unmarried young woman. Often, my male ETA friends or fellow foreigners would want to meet for dinner and I would be forced to decline. Over time, I gently and patiently asserted some independence, balancing what felt authentic to my own identify and what was respectful to my host community.

There were also surprising moments of connection. When my 16-year-old students and colleagues discovered that I used to be a ballerina, they were eager to involve me in the Javanese dance extracurricular program. I attended class after school once a week with them in an un-air-conditioned administrative office. I struggled to catch the dance movements by sight, because my fledgling language skills left me unable to ask questions about style. Our instructor would patiently adjust my arms by touch and my students would practice their English, incorporating vocabulary from our lessons on parts of the body to guide my movements. By the end of each class, we were all laughing at my fumbling attempts. In time though, I became good enough to join the group performance at the annual town celebration.

Gambyong is a traditional Central Javanese dance typically performed by a group of young girls to welcome visitors. Performers don yellow and green batik to symbolize prosperity and fertility. The dance itself is characterized by graceful hand movements, scarf flicks, and a smooth squatting far removed from the plies and grand jetés of ballet.

That dance exemplified cultural ambassadorship and fostered curiosity in multiple cultural directions. I learned the significance of demureness in Javanese culture and discovered the layers of rituals and traditions involved in Javanese ceremonies. Getting fitted for my costume was an introduction to the intricacies of batik fabric, inspiring me to collect batik from each island I visited. The informal rehearsals established a trust between me and my students which couldn’t blossom in the classroom. They felt able to ask me complex questions about myself and my culture which they were intimidated to express in front of their peers, all because we had discovered a common appreciation for dance. Gambyong also helped me integrate myself into other Indonesian sub-cultures.

When I moved to North Sumatra in my second year, where Javanese dance is not a traditional practice, my knowledge of gambyong was proof that I had a genuine interest in getting to know my new community. My host mom, a university professor specializing in traditional Sumatran dance, was ecstatic to discover my passion for Indonesian dance forms and immediately invited me to one of her classes. Because of gambyong, we developed a deep and lasting friendship. I did not come to Indonesia to be a dance student. But as I learned through the Fulbright program, being a cultural ambassador is not only a 9-to-5 job. It demands constant awareness of and involvement in your new environment, recognizing that every moment is an opportunity to foster curiosity in each other. Over time, I fully embraced my role as a citizen diplomat, recognizing that such an experience is both challenging and rewarding precisely because there are no limits to the opportunities to create people-to-people, cross-cultural connections.

Kelsey Figone

Kelsey is a Program Associate at PYXERA Global where she manages programming and logistics for Global Pro Bono teams worldwide. She works with cross-cultural teams to facilitate successful skills-based International Corporate Volunteer programs.