“This isn’t 15,000 incidents of eating bushmeat,” Paul Farmer said. “It’s weak public health systems.”

Prior to his remark, I thought that contracting Ebola was a death sentence, but Farmer corrected my assumptions. “Don’t believe anyone who tells you that case fatality is higher than 10 percent,” he insisted. “These are people dying of untreated shock. That means it’s a supply-chain problem.”

UNICEF conducts door-to-door campaigns to map active cases of Ebola in Tewor district, Liberia. To keep track of the homes visited, the team writes details on the walls of the houses. Photo Credit: UN/Martine Perret

I have admired Farmer’s leadership in public health for more than a decade, but this was the first time I had the chance to hear him speak firsthand. Just off the plane from the hot zone, Farmer presents as an affable uncle, but the issues he describes are deadly serious. “This is not the first zoonosis to jump from animals into humans and then go global,” he remarked, gesturing at past outbreaks of SARS, avian flu, mad cow disease, and swine flu. Ebola, he said, is a public health crisis, driven by the absence of strong public health infrastructure.

On December 3, 2014, Farmer spoke to a group of more than 100 stakeholders at a day-long event that sought to improve the private sector’s response to the Ebola epidemic. Representatives from General Electric, Western Union, UPS, GSK, IBM, and others were in attendance, as well as key leaders of public sector institutions, including Ron Klain, White House Ebola Response Coordinator, and others from The World Bank and U.S. Department of State. The event was convened by a group of nonprofit stakeholders that included Points of Light, CECP, PSI, CollaborateUp, and PYXERA Global.

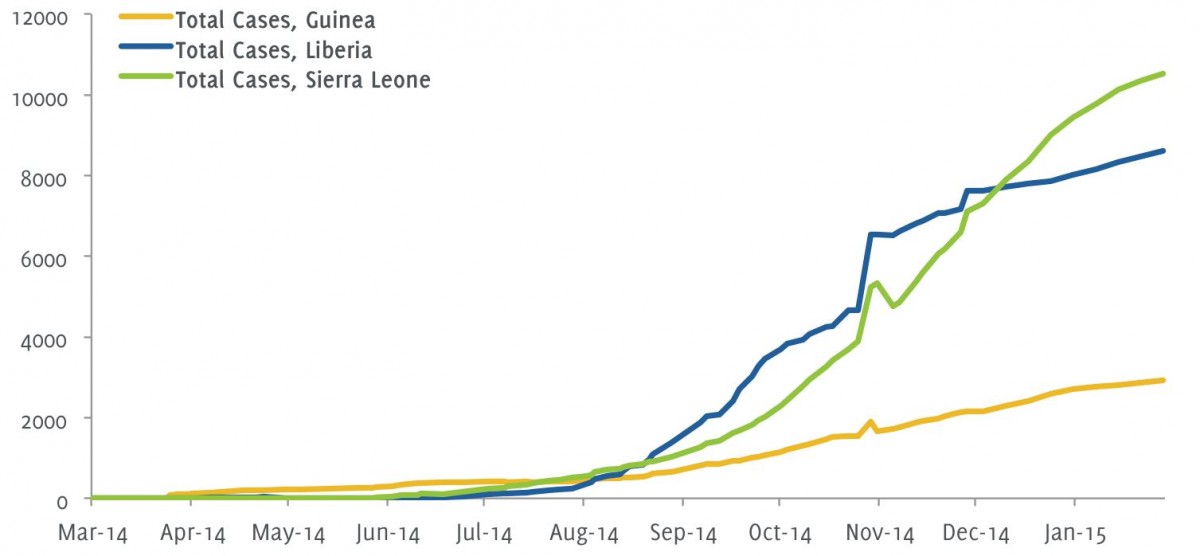

The day before the event, the number of people infected with Ebola surpassed 17,000; the fatalities totaled just over 6,000. Moussa Abbo, a Cameroon native and PSI’s Senior Regional Director of West and Central Africa, spoke on behalf of those on the continent. “We at PSI believe the private sector plays a key role in addressing pressing issues in the world,” he said. “This Ebola outbreak has shown how vulnerable we are.” Abbo called on those convened to take a long view. “We need to share our knowledge and resources across the world. When this crisis is over, we need to continue working together, not to chase this issue, but to address it from the roots.”

David Barash, the Chief Medical Officer and Executive Director of Global Health Programs at the GE Foundation, is an emergency physician by training who still works in his local ER one shift a week. He shared Abbo’s excitement for the potential for collaboration. “I haven’t seen a private sector group come together like I’ve seen it around Ebola,” he said. “Let’s think about how we can do this in the long term.”

I left the event that day overwhelmed by both the substantial commitment of the private sector to respond to the disease and the short-sighted nature of the response. Many organizations were extremely motivated—and rightly so—to support the immediate need for personnel and resources, but few had a clear picture of the road to recovery.

Today, the number of cases of Ebola in Liberia has dropped almost to zero, and the case load in Sierra Leone and Guinea is declining every day. Soon, the immediate effects of the Ebola epidemic will be forgotten, disappeared from the headlines once the disease is fully contained. Yet, in many ways, this simply marks the beginning of a much longer effort to rebuild after the onslaught. Though it may seem the fight is over, the road to recovery has only just begun. Supporting the economic resilience of those countries most affected will require a sustained commitment well into the next decade. The details of how bears further examination.

Fighting Ebola from the Ground Up

It has been more than a year since Emile Ouamouno, a 2-year-old boy epidemiologists identify as Patient Zero, contracted and died from the latest outbreak of the Ebola virus. Since then, more than 23,000 people have contracted Ebola, and over 9,300 have died. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent to respond to the disease, and many millions more are earmarked for the future.

More than 23,000 people have contracted Ebola, and over 9,300 have died in the last year. Photo Credit: UN/Martine Perret

I considered Farmer’s insistence that the disease is a problem of supply-chain management. In much of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, high-speed roads, vehicles, sterile needles, saline, blood banks doctors, and otherwise well-resourced facilities are in short supply, handicapping the countries’ ability to effectively contain and treat the disease. I also investigated how Ebola kills. The disease attacks the immune system, using our own immune cells to attack the body’s defenses. The body’s last-ditch response to this attack leads to organ failure. Intravenous fluids and blood transfusions, two simple interventions easily administered in every ICU in America, can dramatically improve a patient’s ability to survive, providing vital reinforcement to the body’s natural immune response, and staving off a lethal immunological storm. With the right reinforcement, the body continues to fight the virus slowly, to survival. In essence, a person’s life depends on their prompt diagnosis and rapid treatment, the two critical supply-chain breaking points.

Unfortunately, health systems in many parts of West Africa prior to the outbreak were already notoriously weak. While private clinics offered some care for treatable ailments, according to World Bank data, mortality from all ailments is higher than in more developed markets.

These countries also lacked doctors and public health workers. According to Farmer, Liberia had fewer than 50 physicians practicing in the domain of public health prior to the outbreak. As the disease began to spread more rapidly in the summer of 2014, the situation became increasingly dire. Unprepared to handle a highly contagious disease, many private healthcare facilities closed their doors. Afraid of contracting Ebola from colleagues and neighbors, many small businesses folded. In Sierra Leone, the two preeminent mining corporations, London Mining and African Minerals, shuttered their operations. Worse still, the international community was slow to respond. A coordinated international response didn’t crystalize until the U.S. Africa Leaders’ Summit in Washington D.C. in early August 2014, nearly eight months after the first fatality.

Collateral Damage and the Domino Effect

The catastrophic effects of the Ebola epidemic are both complex and intertwined. To fully understand the extent of the resulting challenges, I asked healthcare professionals in West Africa and the United States, as well as investors and economists attuned to the fiscal and economic realities. With limited information available on the epidemic in Guinea, the bulk of my research focused on Liberia and Sierra Leone.

I spoke with two African medical professionals directly affected by the epidemic. Dr. Stephen Dzisi, a Ghanaian doctor who received his post-medical school training in Germany, has been serving as a Public Health Institute Global Health Fellow with USAID in Monrovia, Liberia, for the past two-and-a-half years. When Dzisi arrived in Liberia in 2012, he was shocked by how the consequences of the 14-year civil war still plagued the country. Even though Liberia was dedicating 10 percent of its annual budget to public health, the country’s health system was inherently fragile. “One case of Ebola crossing the border from Guinea, the entire system crumbled because of the fundamental weakness,” Dzisi said.

At the height of the epidemic, more than 80 percent of community clinics in Liberia closed down due to fear among health workers and community distrust. The country’s health system was not prepared to handle the onslaught of a contagious and deadly disease. While health resources in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia have focused on the neediest patients—those suffering from Ebola—the rest of the population has suffered from common ailments that have gone untreated as a result.

Two critical statistics help quantify the epidemic’s effect on the health of non-Ebola patients. In Liberia, immunization has dropped significantly for children under the age of one. Prior to the outbreak, Dzisi said, 88 percent of children in Liberia under one had received the vaccine that protects against diphtheria, whooping cough, and tetanus. “By December 2014,” he said, “this number had dropped to 49 percent.” In maternal health, the landscape is equally grim. According to Dzisi, incidence of maternal fistula more than doubled between January and December, 2014.

Two critical statistics help quantify the epidemic’s effect on the health of non-Ebola patients. In Liberia, immunization has dropped significantly for children under the age of one. Prior to the outbreak, Dzisi said, 88 percent of children in Liberia under one had received the vaccine that protects against diphtheria, whooping cough, and tetanus. “By December 2014,” he said, “this number had dropped to 49 percent.” In maternal health, the landscape is equally grim. According to Dzisi, incidence of maternal fistula more than doubled between January and December, 2014.

Dr. Abdullah Daniel Sesay, a Sierra Leonian doctor, is also a member of the country’s parliament. When I spoke to Sesay, or Doctor “A-B-D” as he is known to friends and colleagues, he was quarantined in his home after returning from a session of parliament to find that someone in his neighborhood had likely been exposed.

Prior to the outbreak, Sesay ran a small community clinic with 44 beds in Makeni, one of Sierra Leone’s larger cities. As the epidemic started to escalate, the clinic closed due to insufficient resources to effectively diagnose and treat Ebola, as did most private clinics in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

As a member of parliament, Sesay is well-versed in the economic challenges the epidemic has wrought. “To break the chain of dead, the government had to create traveling restrictions,” he said. “At the end of the day, this had a negative economic impact.” According to Sesay, prior to the epidemic, Sierra Leone funded 72 percent of its national budget from domestic revenue. Today, the collapse of the mining industry and overwhelming loss of jobs have forced the country to revert to an economy that is largely donor driven. “People are dying of hunger because of the harvesting restrictions,” he said. “Thousands of orphans have nowhere to go.” The debilitating economic environment makes it that much harder to defeat the disease.

Sesay summarized the bleak conditions simply: “What has happened with Ebola,” he said, “is just as bad as the civil war.”

This summer, as the epidemic grew more threatening, a team of World Bank economists were asked to estimate the epidemic’s likely economic impact on the most affected countries and on the continent more broadly. The most recent study, based on a combination of cell phone survey data in Liberia and Sierra Leone and other macroeconomic indicators, was released in January 2015.

Workers disinfect homes with chlorinated water where patients with Ebola were treated in Freetown. Photo Credit: UN/Martine Perret

Based on the cell phone survey data, World Bank research suggests that nearly half of male heads of households [46 percent] in Liberia that were working prior to the epidemic remain unemployed, and even more [60 percent] of female household heads are out of work. The implications of this are twofold. First, the country’s primary productivity has been cut in half, as has the government’s income tax base. Sierra Leone’s survey results, though different, suggest other equally calamitous problems. “In Sierra Leone, small enterprises have been going out of business at much higher rates than they did previously. For businesses that are still operating, revenues are down 40 percent,” said David Evans, a senior economist on The World Bank research team.

In both countries, a large majority of people are hungry and rationing food. According to Evans, “Three quarters of households in Liberia are reporting significant food insecurity. This isn’t because of prices but because income has fallen.” Another problem is that domestic food harvests are lower than past years. Harvesting, typically done in large groups, has been less productive as communal activity has been discouraged or banned for fear of spreading the disease.

Job losses and food insecurity have had measurable macroeconomic effects as well. In Sierra Leone, rapid growth in the first half of the year quickly turned to contraction. Prior to the outbreak, Sierra Leone expected 11.3 percent growth, which fell to 4 percent over the second half of 2014. Evans and his team “expect a contraction of 2 percent in 2015,” a profound reversal in economic progress. In Sierra Leone and Liberia, falling commodity prices of iron ore, copper, and cotton have directly reduced government revenues, causing, Evans said, a “double-whammy” effect.

Mykay Kamara, a Sierra Leonian businessman who currently lives in London, has seen this effect firsthand. Prior to the outbreak, he split his time between Liberia and Sierra Leone, supporting business startup and operations management in the energy and mining sectors. “The mining sector has been seriously disrupted,” he said. “London Mining defaulted, African Minerals Limited have had to mothball their operations.” The country’s largest taxpayers, both companies also provided a significant portion of Sierra Leone’s formal employment. Kamara commented on how restrictions of movement have had a significant downgrading effect on both agriculture and trade. “Investors who had planned to spend aren’t spending anymore,” he said.

Kamara, who has visited Sierra Leone since the outbreak, believes that people’s hysteria has had the most significant negative effect. “People are hysterical and fearful about the disease.”

Going to War with the Disease

Repairing the damage to the economies of Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone will require a multi-dimensional approach; eliminating the disease will only serve to stop the bleeding. Overcoming the disease’s ripple effects will require rebuilding and reinforcing health systems and developing a plan for fiscal and economic recovery.

Overcoming the disease’s ripple effects will require rebuilding and reinforcing health systems and developing a plan for fiscal and economic recovery. Photo Credit: UN/Martine Perret

Yet, such reinforcement can be easier to promise than to deliver. In August, the GE Foundation deployed a $2 million grant to support Farmer’s Partners in Health in Liberia with Last Mile Health and Sierra Leone with Well Body Alliance. The funds were used to train 500 clinical health workers and 800 community health workers, who educate communities about sanitation and post-mortem practices to stem the spread of the disease. This infusion of newly trained talent staffed 47 health centers and one Ebola Treatment Unit with 50 beds.

While Barash is happy with what the GE Foundation funding would be able to accomplish, he acknowledged that the grant was hardly enough to stop the bleeding. So he also formed a business response team within GE to determine how the company could best provide meaningful long-term help. At the December event, he announced that GE would be contributing substantial in-kind support that will include healthcare equipment, water and power systems, and important software solutions.

The goal is that the in-kind assets will shore up medical systems after the crisis passes. “Ultimately all the equipment we are donating will go towards systems strengthening more than towards the immediate response,” which he argues, has a greater impact. “The epidemic provided an opportunity for the Foundation to meet a broader mandate to support systems strengthening in West Africa.”

Most epidemiologists recognize that, while this outbreak of Ebola was especially severe, it is unlikely to be the last. For Barash, there are two challenges that must be addressed to ensure an epidemic of this magnitude is preventable in the future. The first imperative is to build a strong public health foundation, “putting a public health infrastructure together that prevents outbreaks, or allows people to respond to outbreaks quickly,” he said.

But infrastructure alone is not enough. Success and failure in an outbreak scenario depends deeply on the people in charge. Barash noted that management training is often significantly lacking for health professionals in emerging markets. “Our experience is that in developing countries there is a gap in terms of leadership and management skills and there’s a big role that we can play in making that sustainable,” he said. During his first trip to Africa in November 2014, he heard this articulated firsthand by hospital administrators in Kenya and Rwanda.

To address this, the GE Foundation currently underwrites the Ministerial Leadership in Health Program, jointly administered by the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and the Harvard School of Public Health. This program provides leadership training to African ministerial leaders in health and finance. In the future, he hopes to expand such training and support to the community level, where the need is also critical. “What we really want to do is support hospital leaders and the people who are actually on the ground doing the hardest day-to-day work,” Barash said.

Treating the Symptoms and the Ailment

While companies like GE and organizations like Partners in Health have focused on strengthening the country’s health systems and infrastructure, the economic view is still bleak. In mid-January, Kamara traveled to Freetown, Sierra Leone, to participate in the government’s efforts to craft a 2015 post-Ebola economic recovery plan. In his view, his country’s effective recovery will require three key points of reinforcement.

A group of women attend a session on facilitating community acceptance of new Ebola surveillance, clinical care, and burial procedures in Freetown. Photo Credit: UN/Martine Perret

“First, we need to bolster the financial services sector,” he said. Capitalization and liquidity have suffered under the financial strain. Currently, Kamara says, a third of the country’s debts are not being paid.

The country also must address the dramatic reduction in industry that has shrunk its tax base. “You need budgetary support to the government, because of the shortfalls coming from the companies that have reduced their profits,” he said.

Lastly, multinational corporations must begin to consider how to re-engage as investors, especially in tourism, agriculture, and mining, where the economy has been the hardest hit.

In addition to these key economic drivers, Kamara noted the significant handicap small and medium enterprises (SMEs) must overcome to maintain their operations. “You need a lot of support for SMEs, who need technical assistance to help them,” he said.

According to Evans, the World Bank is doing just that, financing a program of about $1 billion to contain the epidemic and to address its economic effects. The investment has two parts—providing $500 million in support for health workers, as well as a platform that helps foreign health workers enter the affected areas quickly and effectively. “On the economic side, the International Finance Corporation has a $450 million project that is providing support to small and medium enterprises across the three countries.”

Evans estimates the fiscal gap across the three countries is about half a billion dollars, or close to five percent of their combined GDP. That large fiscal gap will likely have a dramatic effect on non-health related infrastructure. Sierra Leone and Liberia in particular will require significant budget support to overcome the fiscal shortfall caused by declining tax revenue and an inordinate level of expenditure both countries directed towards Ebola response.

Kamara is disheartened by the return to a donor-funded economy after so much sustained growth. “We are back to an economy that is less private-sector run and more donor-funding run, which is similar to what we had during the war,” he said. “It’s not the right kind of economic growth.”

Of course, the best antidote to a donor-driven economy is private-sector investment. Evans urged companies to invest bullishly sooner rather than later. “Organizations that are considering investment may be hesitant in the wake of the epidemic, but I would encourage them to be bold in the face of uncertainty,” he said.

To that end, Barash hopes to help the Ebola Private Sector Mobilization Group, of which GE is a part, to think collaboratively about the way forward. Already, companies like UPS, Pfizer, Apple, and Intel have agreed to work together to better coordinate their response to the epidemic. But Barash wonders why their efforts must remain solely focused on the disaster at hand. Instead, he wants the group to collaborate on long-term development. While collaborating with competitors may present some challenges, Barash insists a coordinated effort need not constrain a competitive market. “Why shouldn’t GE sit at the table with our competitors to figure out how we solve the problem? We can compete in business, but for the better of public health, especially in the setting of a disaster like Ebola, we should collaborate,” he said.

Efforts are also underway to establish an African Center for Disease Control, making the continent less dependent on support from the U.S.-based CDC. The African Union is coordinating the effort, with high-level support from First Lady Sizakele Zuma of South Africa. Currently, the African Union hopes to bring the initiative online by 2016. The World Bank has also pledged financial support for the undertaking.

Paving the Road to a Healthier Future for West Africa

For their part, both Sesay and Dzisi, two men with a similar view of the problem in Liberia and Sierra Leone, remain optimistic about the future. When I spoke with Dzisi in early February, Liberia was on the verge of zero cases. “We’ve reached the point in my view where we need to strike one more time at trying to get the regular health resources back,” he said. “The perspective is starting to shift to the longer term solution to the problem.”

Farmer says Ebola is a public health crisis, driven by the absence of strong public health infrastructure. Photo Credit: UN/Martine Perret

Dzisi rejected the idea that Liberia should wait until Ebola is gone before it tackles larger health problems. By then, he worries, the international community may be distracted by the world’s next crisis. “Near zero is good enough to work on rebuilding the fundamental health system,” he said. “One, we still have everybody’s attention, including the Ministry of Health, the UN, the international bodies. We still have the opportunity to tap into a lot of resources. If we want to wait for zero cases, as soon as we get to zero cases, we will lose a lot of attention. And this is a country confronted with a huge human resource gap.”

Eighty percent of the health facilities in Liberia that were closed prior to the epidemic are now reopened, though not all services available prior to the epidemic are being offered. “If we go back to business as usual, it’s just a matter of time before another disaster strikes and we are back on our knees,” Dzisi said. “Now is an opportunity to go back to the drawing board to create a more resilient health system that is able to withstand a shock.”

Doing so requires identifying the system’s major weaknesses. To that end, Liberia’s Ministry of Health is leading a health system assessment across the country, looking at its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Dzisi is on the committee for service delivery, supporting this process through his work with USAID in a variety of ways. Once the final report is released this April, the government will begin to look for resources to fill the gaps that have been identified.

For his part, Barash believes that prosperity and growth in any context rests on a three-legged stool of health, education, and infrastructure. “You have to have a healthy population to have economic growth,” he said. “In the crisis setting of Ebola, many workers were rightfully focused on protecting themselves and their families. Work became a secondary need and even a possibly risky proposition.” Getting back to early 2014 growth targets will require reinforcement on all three legs of the stool.

Farmer, for all his admonitions, is optimistic about the future, too. At the December event, he rallied those convened to take heart in a future of partnership. “I am full of optimism about how we are going to turn this around. I am looking forward to living up to our name,” he said, “as partners in health, in the long term.”

As international attention for the epidemic wanes, the persistent problems that have developed as a result will fade from view. The Ebola epidemic represents a dramatic and tragic loss of human life that many will mourn for years to come. Yet, a circumstance of such misfortune also offers a rare opportunity. The international development community can choose to do things differently, to see the next problem as it has begun to emerge, and to support both an immediate and sustained response. With help from a broad range of committed international stakeholders, perhaps Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone can right the three-legged stool, laying a strong foundation for the bright future ahead.

Feature Photo Credit: UN/Martine Perret

Alicia Bonner Ness

Alicia Bonner Ness (@AliciaBNess) is the editor of the The New Global Citizen, where she seeks to showcase the impact of beneficiaries and implementers alike, empowering all those engaged in furthering social good to learn from one another. She is also the Communications Manager at PYXERA Global.

Pingback: What are the consequences of the recent Ebola epidemic in West Africa? | Africa: Past to Present